| |

|

Libyan

Constitutional Union

http://www.libyanconstitutionalunion.net

&

http://www.lcu-libya.co.uk

|

|

|

|

|

|

بسم الله الرحمن

الرحيم

The Libyan Constitutional Union:

Its Establishment and Development

A Documentary Article

by Mohamed Ben Ghalbon

(Summary Translation from Arabic)

| |

Readers of this series of documentary articles will be able

to examine a narrative of historical events that took place in

an important period in the history of our country. I am of

the opinion that it is a duty to the homeland to record and

publish these historical events, so that we do not lose

contact with that important part of our contemporary history.

As the narrative of these events deals with the stances of

some individuals who were active participants in them, it

becomes essential that these stances be recorded in their

proper contexts. The intention behind the publication of

these accounts, almost a quarter of a century after their

occurrences, is not to criticise or denigrate the individuals

who were active participants in them. Rather, this publication

is a modest attempt to uncover and clarify part of our history

that has passed over in silence. Thus, I hope that this aim

should not be misconstrued and the writer of this article

should not bear the responsibility for the cynical

interpretations by others of its content. |

|

Part (1)

(First published in Arabic on

11th June 2006)

Quest to obtain King Idris’s consent

Preamble

The

idea of writing this documentary article was dictated by Mr Faraj

El-Fakhri’s enquiry in his article “The Squandered

Opportunities” in which he asked:

“Why did the LCU not

succeed in attracting The Libyan opposition groups around its

slogans during that early period [1981]? These are the same slogans

adopted and raised today by Libyan opposition movements. Chief

among these slogans was the call raised by the LCU at its inception

to rally around

King Idris I,

who was still alive then. This in reality was a call to rally

around the symbol of constitutional legitimacy of Libya

[1]

Mr

El-Fakhri

continued his article by expressing the hope that the LCU founder

members would undertake the task of explaining all the circumstances

that led to the squandering of the

opportunity that the

LCU provided the Libyan opposition with, in asking them to unite in

support of the Libyan Constitution. This demand which was

ignored 25 years ago has now become a key demand of the Libyan

opposition

[2].

Mr El-Fakhri

further expands his narrative with the enquiry as to why the LCU was

not successful in realising its goals (mentioned above), and

followed that by asking another question of two parts:

o

“Was this failure due to the incompetence and the inability of

the leadership of the LCU, at that time, to explain and communicate

their idea to the others?

o

Or does the shortcoming arise as a result of the conflict of

concepts and ideas among the competing opposition movements?”

He concludes by asking

the founders of the Libyan Constitutional Union to provide answers

and explanations to an era full of events, facts and secrets which

in their totality are the reason behind “squandering that

opportunity”

[3].

Previously, I had

always had the intention and the resolve to talk about this

important era in the history of our homeland; however my fear for

the hurt that this might cause to the people who participated in its

events, due to their dishonourable stance, has prevented me so far

from doing so. I constantly delayed talking about this era and

waited for the time when the circumstances are right, more

accommodating and accepting for such an action. I consider the

current circumstances may be more suitable to deal with these

important events in our homeland’s recent history.

When I resolved to have

a written record about these important and thorny events I thought

it sensible to suggest to Mr Farag Elfakhri, whose

questioning gave rise to writing about these events, that he puts

together this record in a suitable writing style.

I immediately

telephoned Mr El-Fakhri and suggested we meet to answer his

line of questioning, and asked if it was possible for him to write

and edit the answers then to send them to me to review for

publication on the Libyan web sites. Mr El-Fakhri’s response

to undertaking this difficult task was agreeable and welcoming. We

agreed to meet in Leeds to start the narration of the information of

this period to him while recording it on cassette tapes. Our

meetings started in October 2005 (Ramadan 1426) in the presence of

my brother Hisham. The narration took six separate meetings.

Furthermore, the

narrative will be in the first person pronoun in the same fashion it

was received by the editor.

**

***

**

The

beginning

When I decided, in the

early 1980’s, to convert the idea of establishing the Libyan

Constitutional Union, which was ripe in my mind for some time,

into a reality it was imperative that I get in touch with the late

King Idris (may Allah bestow His mercy on his soul) who

embodied the Constitutional legitimacy to rule Libya. He was

usurped of that rule by a group of low ranking officers who staged a

coup d’etat in September 1969.

It was important that

this should be the first step, as the issue of the Constitutional

legitimacy to rule is part of the foundation and one of the

principles upon which the idea of establishing the Libyan

Constitutional Union was based.

So I embarked on

attempting to gain access to King Idris. That was not an easy

task. It was an ordeal with many obstacles that I had to overcome.

The late King had been

living in Cairo as a political refugee since the staging of the

military coup in Libya, in a villa in the suburb of Dokki in Cairo,

which was assigned to him by the Egyptian Office of the President.

He was forbidden by the Egyptian authorities to deal with political

affairs or to receive any person active politically against the

military government in Libya. A team of Egyptian security

personnel, headed by a veteran officer was appointed to serve,

protect and keep a continuous watch over the king.

It was very difficult

to pass through the security cordon imposed on the King’s residence

and to reach him through the normal means. The very close watch over

the King’s person and his movements isolated him from the outside

world except for few relatives or old close friends.

Therefore, there was

no way for me to get in touch with the King except through one of

these few persons who used to visit him and his estimable family.

**

***

**

Contacting the King:

After getting in touch

with many in the circle of my personal connections and looking

carefully and persistently for information from every source, I

managed to

approach an

honest and dependable person from among the few who had direct

contact with the King. I asked this person to convey a message from

me to the King. I stated in this message my wish to visit His

Majesty to talk to him about my resolve to found The

Libyan Constitutional Union, and to renew -on behalf of my self,

my family and collegues- our pledge of allegiance to His Majesty as

the constitutionally legitimate ruler of

Libya. And to proceed

thereafter -with his permission-

towards urging Libyan

notables from various regions of the country to do the same in

public – by publicising it in the international media.

It is important to

emphasise that

the pledge of allegiance here does not imply that

the Libyan people’s pledge of allegiance

to the King before Independence had withered or that it had lost its

legitimacy, on the contrary, The King’s constitutional legitimacy

was rooted in the unanimous desire of the entire nation for him to

be their King and this constitutional legitimacy could not be

revoked by an illegitimate act.

Renewal of the pledge

of allegiance means the affirmation of the continuity of the old

pledge of allegiance, and proof that it has not lost its holding

force, for the new pledge of allegiance – in its essence- is

considered a symbolic pledge of allegiance re-affirming the old one,

and referring to its genuine legitimacy. Proving that the pledge of

allegiance to the King and calling on him to resume his role as

ruler of the country is a legitimate and constant right that time

has not erased, nor revoked by the usurping of authority by force.

And so this

praiseworthy person continued to convey my successive oral messages

to the late King. This had lasted for many months approaching a

whole year. I was careful in these messages to King Idris to

affirm my hope that he might not deprive his people of his blessing

and the bestowing of his legitimacy on our call upon him to be the

legitimate ruler of the country.

In all my messages to

King Idris, I was appreciatively and considerately aware of

his ascetic way of life, his reluctance to rule or hold power and

his loath to return to office and resume its burdensome duties.

However, there was an overwhelming necessity imposing itself

on this case and making his approval inescapable This necessity

went beyond the personal desires latent in this pious and devout

King, and would not accept from him –or anybody in his station-

compliance with his own personal preferences. This necessity

dictated that the late King consent to providing, the sacred task of

liberating the home land, with his blessings.

If it had not been for

the above mentioned necessity, I would not have dared to

approach the devout and pious king on the subject concerning the

legitimate right to rule the country

There was therefore a

heavy price for King Idris to pay, as he had no interest to

rule at his advanced age and he wished to spend the rest of his life

in worship and meditation.

Therefore, I took care

in my oral messages to King Idris to emphasize that his

consent to give this noble task his blessings was imperative to open

the way to liberate Libya. Thus providing this endeavour with legal

and legitimate support which the world would pay attention to. And

on the other hand this approval would create the leadership and

symbol which the Libyan Opposition was in dire need of.

In my successive

messages, I affirmed to the late King my full consideration to his

weak health and old age. Further, at that time I thought that, and

in keeping with my belief that only Allah knows when one dies, The

Creator might not give him the time to witness the

struggle for the liberation to its end.

However, it was of the utmost importance to obtain his blessings

for the call upon him to be the legitimate ruler of the country, for

he would provide, by giving his consent, blessings and an honourable

seal to the struggle to regain the freedom of the country with its

necessary means and materials. And even if Allah willed that he

would die before the end of this struggle, then the struggle would

definitely continue with the authority derived from his

constitutional legitimacy.

I made sure that my

oral messages were detailed enough to cover all aspects of this

matter which would neither strain the King nor burden him with too

much responsibility. Further, it would not breach his undertaking to

the Egyptian authorities concerning his non-involvement in politics.

On the spiritual

front, I was adamant that he not leave this world before remedying

the hurt and injury he was feeling as a result of his people’s

failure to defend him when he was affronted by the dregs of

society. I was seeking his forgiveness of the Libyan people in the

hope that through it they would find a way out of their ordeal.

So at this stage it

only remained to meet His Majesty, and this meeting would implicitly

mean his approval of the content of my messages. This was the

beginning of another arduous journey, for as I have explained

before, his meeting was very difficult to arrange. For there were

not only the Egyptian security apparatuses watching the King 24

hours a day but also “Haj Mohammad El-saifat” who, as a result of

his old relationship with the King, gave himself the right to decide

who should visit the King and who should not.

To be continued….

Mohamed Ben Ghalbon

chairman@libyanconstitutionalunion.net

8th July

2006

[1]

Part two of “The Squandered Opportunities”, posted on “Libya Our

Home” on 23rd September 2005.

http://www.libya-watanona.com/adab/ffakhri/ff23095a.htm

[2]

Ibid

[3]

Ibid |

|

|

|

Top of

the Page

Original Arabic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This part was published on the

following Libyan sites |

|

"Libya

Our Home" ,

Libya Al-Mostakbal"

, "Al-Manara"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

بسم

الله الرحمن الرحيم

Part

(2)

(First

published in Arabic on

14th June

2006)

Quest to obtain King Idris’s consent

Paving the way for a meeting with The

King:

As

I have previously explained, having passed to the King my messages

regarding my intention to establish the LCU, all that was remaining

was to meet His Majesty to renew the allegiance and then announce

the establishment of the Libyan Constitutional Union. I have also

mentioned in part 1 that meeting the King was neither an easy matter

nor an easily attainable goal, for to meet him, one had to overcome

several difficulties, namely getting through the vigilant Egyptian

security, or gaining the acceptance and the consent of Haj El-Saifaat,

who gave himself the authority - by virtue of the old relationship

that he had with the King- to vet the individuals who would like to

visit the King and would decide who could see him and who could not.

Fortunately, I did not

have to go through either of these two channels. The visit was

arranged, with the king’s permission, by the person who acted as the

link between the King and I. Furthermore, this visit would not be

an occasion where I repeated what had already been communicated to

the King through this intermediary. The meeting would finalize the

aspects contained in my messages to him, for me to pledge my

allegiance and for him to give his blessing to the establishment of

the Libyan Constitutional Union.

The intermediary and I

agreed to meet in Egypt during the month of August (1981). We

agreed that I would wait for this person (the intermediary) to

telephone me at my father’s house in Alexandria. I had travelled

from Manchester to Alexandria during the agreed upon period but

after sometime there I was not contacted as previously agreed.

Due to my good

knowledge of the extent of honesty, nobleness, generosity and good

intentions of this individual, I was sure a situation must have

presented itself that prevented the contact

I found myself in a

dilemma; I was not in favour of resorting to either of the two

channels mentioned previously in this regard, due to the sensitive

nature of my visit to The King, which made it unwise to reveal it to

anybody yet. However, I was forced to contact Haj Mohamed El-Saifaat

who knew the intermediary, and asked him to pass my phone number to

our mutual friend to contact me urgently in Alexandria, for I had

been entrusted to deliver something to that person prior to my

return to the UK. I made this excuse to Hajj El-Saifaat to avoid

telling him about my previous and next contact with King Idris.

Shortly afterwards the

intermediary contacted me and apologised profusely for not getting

in touch with me in the specified period due to losing my telephone

number, and that all attempts to get my number from others had

failed. The intermediary informed

me at once that an appointment had been arranged for me

to visit the King to finalise the noble

aim I dedicated my self and my team to accomplishing.

On the specified day

of this visit, the intermediary arranged a meeting for me with Mr

Omar Shelhi, who I was informed, had volunteered for the task of

accompanying me, hence

facilitating my entry to the King’s residence

through

the Egyptian security apparatuses.

That would be the first time I ever met Mr. Omar Shelhi.

**

***

**

In the presence of the King:

I met

Mr. Shelhi on the specified date at a predetermined location. From

there we went in his car to the King’s residence in the suburb of

Dokki.

As soon

as the car stopped in front of the villa we entered through a gate

that was surrounded by Egyptian security men who greeted and

welcomed Mr. Shelhi, whom they knew very well and therefore neither

stopped him, nor checked the identity of the person who accompanied

him.

As we

entered the sitting room, my companion introduced me to King Idris

and Queen Fatima whose warm and

affectionate welcome

made me feel very happy and at ease.

I addressed the King

and expressed my feelings of deep sorrow and regret for the

suffering and pain he had to endure in his exile away from his

homeland and people for whom he spent his entire life to achieve

their independence. I dissociated my self from what the dregs of

society had inflicted on him, and made clear to him my profound

awareness of his grand spiritual rank. I then expressed my renewal

of allegiance to him as the King of Libya.

I told him I would

like to know his verdict concerning what he had examined regarding

the matter of the establishment of the Libyan Constitutional Union

and the call upon him to be the legitimate ruler of the country.

The reply of the pious King was brief but eloquent and decisive. He

looked at me and quoted from verse 3 of Surat Al-Fath:

“May Allah make

your victory an impregnable victory”

"

ينصُرَك الله نصراً عزيزاً

I kissed the King’s

hand and departed, totally overwhelmed with happiness and joy, I

felt my feet could hardly touch the ground. My arduous efforts to

obtain his consent and blessing to continue in this patriotic and

task were crowned with success.

Mr Omar Shelhi

accompanied me to the outside gate of the villa and as we got into

the car he asked me about my destination. When I replied he said

that the distance was short and he suggested that we could walk it

together.

I understood at once

that he wanted to talk to me about the subject matter that I came to

see the King for, and walking together would provide him with the

longer time needed for that purpose.

As I expected, as soon

as we got out of the car and started walking my companion asked me

if I was aware of the enormity and the gravity of the undertaking

for which I had endeavoured to obtain the King’s approval. He

continued with answering his own question and added that; if I was

not aware, I was attempting to cross a minefield.

I told him that I was

quite aware of what he meant and that I understood perfectly the

nature and magnitude of the task I was about to undertake. And I

ask Allah’s help in order to succeed to do our country, which was

suffering under the hated military regime, a lot of good. He then

said to me that this task would not only require me to defend the

monarchy as embodied in the person of the King, but also to defend

the entire regime of the monarchy i.e. its personalities and

symbols, especially those who were very close to him and considered

his clique.

It was

clear from his previous hint that he was aiming to entice me to

adopt the stance of defending him and his family when defending the

King; however, I was clear, frank and decisive in this regard.

I further explained

that I did not consider it to be the most suitable of times to raise

the banner of monarchy in Libya. The coup d’etat regime had

successfully, worked relentlessly with all the state resources at

its disposal to distort the image of such a form of government, and

to level all sorts of false accusations against it. Furthermore, I

told him that he had to bear in mind that the prevalent trend among

the Libyan intelligentsia and the opposition ranged from the

so-called “progressive ideas” in the leftist and liberal tendencies

to the growing religious currents. All of the people of all these

persuasions, at least at that time, did not wish to be associated

with the Monarchy in Libya.

On the other hand,

when I advanced the idea of establishing the Libyan Constitutional

Union and thought about the necessity of obtaining the blessing of

the King for it, because of his constitutional legitimacy as

documented in the codification of a constitution agreed upon by all

of the Libyan nation, I did not envisage that I would be in the

position of defending personalities that had political and titular

offices and positions in the monarchy regime. It was not my

intention to justify or catalogue the mistakes of some of the

symbols of the monarchy regime, for this was not my business and

these personalities could defend themselves if they wanted to. My

task in this regard would be limited to the King and the

Constitution, and may Allah help me in the onerous and difficult

crossing of the minefield and I was certain of the difficulty

involved in doing so.

My

answer above put an end to Mr. Shelhi’s hope of enlisting me to

defend him and his family and consequently ignited his enmity

towards me.

Our

conversation ended at that point, as we reached my temporary

accommodation.

I

thanked Mr Shelhi for his generosity in facilitating my meeting with

the King and he said good-bye to me in a cool manner which he made

no effort to disguise.

To be continued…

Mohamed

Ben Ghalbon

chairman@libyanconstitutionalunion.net

21st

July 2006

|

|

Top of

the Page

Original Arabic

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This part was published on the

following Libyan sites |

|

"Libya

Our Home" ,

Libya Al-Mostakbal" , "Al-Manara"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

بسم

الله الرحمن الرحيم

Part (3)

(First published in Arabic on

1st July 2006)

[2] Announcing the Establishment of the

Libyan Constitutional Union

Introduction…..

It is

important that readers know that during all of my contacts with the

leading personalities of the various Libyan opposition movement, in

exile to publicise the establishment of The Libyan Constitutional

Union and to acquaint them with it,

that at no time did I ever criticise nor attack any of these

individuals. Even when some directed their attacks to me personally,

and spread doubts and suspicion over the reasons, goals and motives

of my clear campaign.

I

restrained my self, from getting engaged in exchanges (verbal or

written), with those who did not follow the etiquette of

constructive criticism and went along a path of hostility and

arrogance that drove them to consider me as their enemy which I was

not. I approached them in the spirit of peace and affability for

the purpose of unifying the ranks under one umbrella forming an

entity that was capable of realising the aim of helping our country

and saving it from the corrupt regime.

Even when

I was forced to take a stand against those who overstepped the

boundary of professional courtesy in their personal attacks against

me and my family, I always confined my responses within decency,

good manners and to the point.

As

I have repeatedly said, my purpose of writing this article is to

record and document important events and stances in our contemporary

history, however, at the same time I affirm that I have been very

careful to write this article and publish it when most of the

people, who participated in these events, are still alive.

This

insures accuracy and truth in recording and documenting the

information. It also requires me to give ample opportunity to those

concerned to respond to the information presented in this article

with respect to their referred stances and allows them to affirm,

refute or add to them.

In

return, I hope that those people who desire to reply or comment on

this article, be bound by the principles of moral responsibility in

their stating of the mere facts without fabrication or distortion.

I

also hope that these people have the moral courage to write under

their real names and not to resort to hiding behind

pseudonyms

making it on the one hand hard to hold them accountable for the

falsehoods they propagate and on the other hand this use of

pseudonyms impairs the chance for everybody to enrich serious and

responsible discussions and dialogues about important events in our

country’s recent history.

*

*

*

*

*

Announcement of the Establishment of the LCU:

The

publicity campaign for the establishment of the Libyan

Constitutional Union started with a greeting card on the auspicious

occasion of the Greater Bairam (Eid Aladha) as it coincided with 7th

October (1981), the thirtieth anniversary of the proclamation of the

Libyan Constitution. It contained the statement announcing the

establishment of the L C U[1],

its motives and aims. It was widely

distributed among the Libyan citizens inside and outside

Libya. The number of these letters reached thousands, for we managed

to obtain lists of names and addresses of a large number of Libyans

residing in Egypt whose numbers then could be counted in thousands.

We

also obtained lists of names and addresses of large numbers of

Libyan students in the United Kingdom and in the United States of

America

[2].

Furthermore, we sent thousands of letters containing the relevant

information to the mail boxes in various Libyan Cities addressed to

fictitious names. These would reach the owners of the mail boxes

without jeopardising the safety of the mail box owners, who could

easily dissociate themselves from these letters, should the

oppressive authorities discover them, as those letters were

addressed to unknown names unconnected to them.

It came to our knowledge through some people from inside the country

that the mailing of these letters had achieved the desired success

to a large extent.

*

*

*

*

*

This was

on the general level, we also endeavoured to contact directly all

the active Libyan opposition groups (some of their members were

already known to us personally), as well as many Libyan notables to

inform them about the newly established Libyan Constitutional Union

through letters containing a thorough explanation of the principles

and aims upon which the Libyan Constitutional Union was established.

We also

made personal contacts through telephone calls, mail and meetings

with the personalities that we had known previously, to inform them

about the matter under consideration and to explain to them fully

the essential nature of the Libyan Constitutional Union and its

planned aims. This was aided by issuing three carefully prepared

booklets, which were sent to the relevant parties in three

instalments in the period between 7 October 1981 and the end of

December 1981.

[3]

In tandem with sending these letters and booklets, there was media

coverage regarding the establishment of the Libyan Constitutional

Union as soon as it was announced.

*

*

*

*

*

Reactions…….

Contrary

to our expectations not many among the dozens of individuals whom we

had contacted personally to inform them about the establishment of

the Libyan Constitutional Union, bothered to respond or to reply.

However, the reactions of those who showed a degree of interest were

diverse.

The

replies were divided according to the level of intellect and

background of the individual concerned. Some of these people who

replied had a high level of moral sensitivity and a sense of

patriotic responsibility, in addition to a degree of intelligence

and heedfulness in grasping the concept advanced by the Libyan

Constitutional Union and the ability to see its ramification on the

future of the national cause.

At

the same time, other reactions had elements of chauvinism and the

preference of personal and political interests at the expense of the

national cause.

Others still, were motivated and driven by tribalism without any

consideration to the interests of the homeland and its essential

causes.

In what follows, I will talk about the various reactions which were

typified by some opposition personalities in exile. These

personalities were contacted and met by the Libyan Constitutional

Union in the period of its establishment and after that.

This

was for the purpose of the unification of all the Libyan opposition

under one umbrella with a program containing the assertion of the

legal legitimacy which would facilitate the struggle against the

ruling military regime through international legal legitimacy and

accord the Libyan cause through effective means capable of toppling

the corrupt regime.

*

*

*

*

*

Omar El-Shelhi

As I

mentioned previously in part 2, my relationship with Mr. Omar El-Shelhi

had grown cold and uneasy. However, our subsequent frequent

meetings at the King’s residence during my regular visits to the

King which I endeavoured to maintain throughout his life, had a

positive effect on this relationship and softened Mr. Shelhi’s

unfriendliness towards me. For, with time and as he followed the

LCU’s publications, and knew me more through these visits, he became

more convinced of my true intentions, and satisfied himself that I

was not an adventurer who would abuse the king’s reputation or an

intruder with an ill agenda. He saw that my coming close to the

King was motivated by loyalty and pure love of the King, coupled

with a genuine desire to benefit the national interest.

With

time, some sort of familiarity had formed between Omar El-Shelhi and

my self, which before long developed to a strong friendship. We

exchanged visits and frequent phone calls. However, this friendship

did not go beyond personal amity, and never involved any sort of

political alliance or co-operation.

During

this closeness to Mr. El-Shelhi, I discovered two

distinctive marks of

his

character. The first was that he has a deep and unrivalled sense of

patriotism towards the home land. The second and more vivid was his

unlimited loyalty and devotion to King Idris.

The second

characteristic, which was clear to every body that had to deal with

him in this regard, had turned to an overwhelming possessiveness of

the King. It developed in him a level of blind jealousy that pulled

him out of the realm of courtesy when he sensed that anybody was

getting too close to the King or rivalling him to the King’s favour.

For

this particular reason, I dealt with him in this area with diplomacy

and extreme tact , and made sure that I would not provoke this

vulnerability.

As such,

there was nothing in the horizon that would muddy this relationship,

until my publication in 1989 of the book “The Life and Times of King

Idris of Libya”

[4]

which was written by Mr. Eric de Candole. That provoked Mr. El-Shelhi’s

enormous outrage and from then till this day he unjustifiably took

me for a bitter enemy

Details of

this episode have no bearing on the subject at hand. I will,

therefore refrain from expanding.

What is

important in this context is the fact that all that friendship and

good feelings that grew between Mr. Shelhi and myself was abruptly

ended by that event, and have turned to hostility that remains till

this day.

*

*

*

*

*

Mohammad Othman Essaid…

As I mentioned above some of the contacted opposition personalities

were characterised by a certain degree of a sense of patriotic

responsibility and a level of intelligence combined with heedfulness

in grasping the concept advanced by the Libyan Constitutional Union

and had the ability to see its ramifications on the future of Libyan

cause. Mr Mohammad Othman Essaid was one of these people.

I had had

no previous acquaintance with Mr Essaid

who was among the first who replied to the Libyan Constitutional

Union contacts by a telephone call from

Morocco where he is a permanent resident. In this telephone call he

expressed his utmost admiration for the idea and the orientation as

formulated by the Libyan Constitutional Union in the letter

containing the above mentioned three booklets.

He

confided in me, in a state of excitement and esteem for the idea of

establishing the Libyan Constitutional Union after reading its

letter, that he had wished that one of his sons had come up with

this enlightening idea.

My

friendship and knowledge of Mr Essaid grew

stronger in meetings repeated with the passage of time and in which

he frequently expressed his support of the orientation of the Libyan

Constitutional Union and its hoped for aims. However, due to his

position as a political refugee it was difficult for him to

participate in any political activity in this regard.

*

*

*

*

*

Abdulhameed El-Bakoosh.

I did not

know Mr

Abdulhameed El-Bakoosh

closely before the establishment of the Libyan Constitutional Union;

however, my relationship with him was deepened to a good degree

after exchanging contacts between us which was crowned later on with

personal meetings in the two cities of Manchester and Cairo.

[5]

Mr Bakoosh was among the first who took care to reply to the

contacts concerning the announcement of the establishment of the

Libyan Constitutional Union. And his reply in this regard was not

only confined to the telephone and written correspondence but also a

personal meeting at my home in the city of Manchester.

Mr

Bakoosh made a telephone call to me in

July 1982 during the holy month of Ramadan. He informed me in this

phone call that he had received my letters dealing with the

establishment of the Libyan Constitutional Union and that he was in

London and would travel to Manchester to meet me and talk to me

about the subject matter under consideration.

To be continued....

Mohamed Ben Ghalbon

4th

August 2006

chairman@libyanconstitutionalunion.net

ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

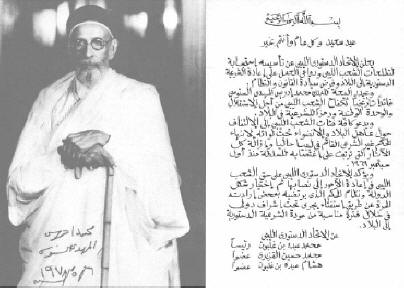

[1]

The Eid (greeting) Card which had been sent to the majority of the

Libyan personalities, contained in one of its two pages the

announcement of the Establishment of the Libyan Constitutional Union

and in the other a photo of King Idris. This photo has a story

which is related elsewhere in this article. Appendix No.1)

[2]

We managed to obtain a copy of lists of addresses of students

studying in Britain and America which belonged to the General Union

of Libyan students (UK branch). My brother, Hisham, was one of its

founder members.

[3]

These booklets were prepared and sent in three consecutive

significant anniversaries of modern Libya. The first one 7 October

1981 which commemorated the thirtieth anniversary of the

announcement of the Libyan Constitution and coincided with the

occasion of the

Greater Bairam (Eid Aladha)

of that year, the second on 21 November of the same year coincided

with the date of the UN resolution that granted Libya its

independence, and the third on 24 December of that year coincided

with the thirtieth anniversary of the independence of Libya.

The reader can examine these booklets which are published/posted in

the Libyan Constitutional Union archive web site whose link is

http://www.lcu-libya.co.uk/aims.htm

[4]

: “The Life and Times of King Idris of Libya”, first published by

the author Mr. E.A.V. de Candole in a private edition of 250 copies

in 1988 as a tribute to his friend King Idris I. The author was

forced to publish it privately in this small number after his

attempts to get a publisher for this book have failed.

Having secured permission from the author, I passed it to my friend

Mr. Mohamed El-Gazieri who translated it to Arabic. I then

published it in 1989 and distributed it free of charge to friends,

researchers and those who have an interest in Libya. I also

provided complimentary copies to numerous public libraries and

University libraries in the Arab and Islamic world, as well as

Europe and the USA. The purpose of this action was to honour

Libya’s great late King Idris El-Senussi by providing researchers

world wide with a credible account of his life compiled by a

credible and close contemporary to the late king. The book

contained important details, which we felt should become a source of

information for writers and historians.

In May 1990 I republished it both in Arabic and English and

distributed it freely on a wider scale in the same manner. The

costs of publication and distribution of the second edition were

shared equally with me by two Libyan patriots who asked for their

identities not to be revealed for fear of persecution from the

Libyan despotic regime.

[5]

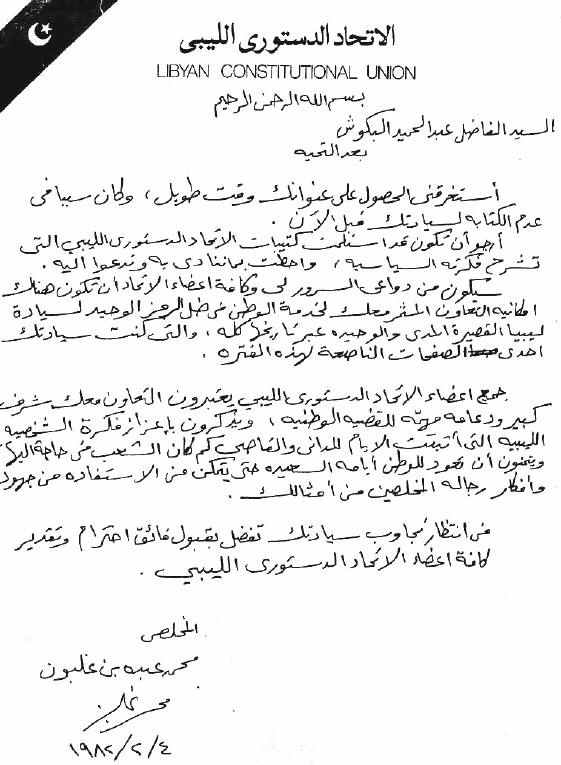

The first letter was sent to Mr Abdulhameed El-Bakoosh on 24

February 1982, to inform him about the program and the aims of the

Libyan Constitutional Union. ( A photocopy and translation of this

letter is attached underneath.)

Appendix No.1)

In the name of God, the

Merciful, the Compassionate.

The Libyan

Constitutional Union hereby proclaims its institution in deference

to the aspirations of the Libyan people and the exigencies of

seeking to restore constitutional legitimacy to the nation and to

re-establish the rule of law and order.

The Union

reiterates the pledge of allegience to King Muhammad Idris al-Mahdi

Sanusi as historical leader of the Libyan people's struggle for

independence and national

unity and as a

symbol of legality for the nation.

It calls upon

all Libyans to rally around their monarch and under his banner to

put an end to the illegitimate regime now existing in Libya and to

eliminate all the consequences that have accrued from its usurpation

of power since September 1st 1969.

The Libyan

Constitutional Union emphasizes the right of the Libyan people to

restore justice and thereafter to decide such form of body politic

and system of government as they may choose of their own free will

in a referendum to be conducted under international supervision

within a reasonable period from the restoration of constitutional

legality to the nation.

A translation of a letter sent to Mr Abdulhameed El-Bakoosh:

The honourable Mr Abdulhameed El-Bakoosh

Greetings!

It has taken me a long time to obtain your address and that is the

reason of not writing to you until now. I hope that you have

received the Libyan Constitutional Union Booklets which explain its

political idea and what we strive to achieve and stand for.

I and all members of the Libyan Constitutional Union would be

pleased if there is a possibility of fruitful cooperation with you

to serve the homeland in the shadow of the only symbol of the Libyan

sovereignty which was short in duration and unique in the entire

history of Libya. Furthermore, you were one of the brilliant pages

of this period.

All the members of the Libyan Constitutional Union consider

co-operating with you a great honour and an important

consolidation

of the national cause and they remember with pride and appreciation

your idea of the

"Libyan Personality"

which time has proven how much the people were in need of and they

wish for the return to the homeland its happy days so that it can

make use of the efforts and ideas of the sincere people like you.

While waiting for your response, estimable sir, please accept the

highest respect and appreciation of the entire members of the Libyan

Constitutional Union

Sincerely,

Mohamed Ben Ghalbon

4/2/1982

بسم

الله الرحمن الرحيم

Part (4)

(First published in Arabic on

15th July 2006)

[2] Announcing the Establishment of the

Libyan Constitutional Union

Cont. Abdulhameed El-Bakoosh:

In the

previous part of this documentary article, I stopped at Mr.

Bakoosh’s phone call from London in which he informed me that having

received our correspondence regarding the formation of the LCU, he

was coming to Manchester to meet me to discuss the matter.

Mr.

Bakoosh arrived at my house in Manchester the following day, and

that was the first time I met him.

After

welcoming the honourable guest first in my house, we moved to the

LCU’s headquarters to discuss the matter in hand. There waiting for

us were Mr. Mohamed Al-Gazieri and my brother Hisham.

We talked

extensively for a few hours about the LCU, its motives and aims.

Our discussion revealed to me that Mr. Bakoosh had, from the outset,

a deep understanding and appreciation of all aspects of this

patriotic endeavour, which was consistent with his renowned

astuteness, high level of intellect and true patriotism. As such,

there was nothing one could add in this context to some one of

Mr.Bakoosh’s calibre.

Therefore,

I wasted no time to propose to him that he become the head and

leader of the LCU, in order to realise its desired goals, and fulfil

the hopes that were now resting on it. I did that for two reasons:

1.

Mr. Bakoosh possessed tremendous political experience, much needed

by anybody on whose shoulders the responsibility of leading the

struggle to return

Libya to

constitutional legitimacy was to fall. Such a task requires certain

political qualifications, polished experience in leadership and

strong regional and international connections, as well as sound and

unquestionable loyalty to the homeland. Mr. Bakoosh possessed all

of these qualities in abundance.

2.

The founders of the LCU were novices to the political stage and

lacked the political credibility, experience and connections which

Mr Bakoosh commanded. One quality they possessed in abundance was

their enthusiasm and dedication to the cause of the homeland, which

motivated and guided them to establish the LCU.

I went on

to assure Mr. Bakoosh that the founders and members of the LCU would

happily follow him and serve under his leadership to achieve the

desired goal.

Mr.

Bakoosh thanked me profusely for my offer, which he saw as a

pinnacle of generosity and selflessness. He then made clear his

inability to accept it because of his distinguished status, which

made it inappropriate for him to accept a position conceded to him

by a group of young people who have no recognised rank.

He went

further in his explanation by saying that the situation would have

been entirely different had the idea of the LCU been his brain

child. Only then would leading this establishment be a natural and

logical consequence. But having the position conceded to him by a

group of unknown young people is something he could not consent to.

In spite

of my total disagreement with all of what my honourable guest had to

say in this context, I continued the conversation with him to get to

the bottom of his reservation. I assured him that his chairing the

LCU would not imply that he was appointed to such a position as much

as it would simply mean that he, himself, had volunteered to lead it

for the sake of the national cause.

He replied by saying that the fact would still appear to others that

it is purely a matter of appointment by the founders of this

organisation, something unacceptable to his prominent status. He

then added, that the only way around this would be for me to

persuade King Idris to publicly appoint him as chairman of the

Libyan Constitutional Union, as he had done previously when he

appointed him Prime Minster of the Kingdom of Libya.

I was certain then that this particular request was the reason that

motivated Mr. Bakoosh to come and meet me.

Due to my

admiration and high regard for Mr. Bakoosh, whom I respect dearly

for his well known patriotism, I did not shut the door of discussing

the matter further with him. However I made an effort to clarify to

him that his request was neither logical nor fair. King Idris did

not have the authority over the LCU in the manner assumed by Mr.

Bakoosh to appoint him as its head. The King’s authority in this

context emanated from the esteem he enjoys in the hearts of the LCU

founders, who would not refuse the King’s request if he were to make

it. However, he would never do that for the following reasons:

o King

Idris did not found the

Libyan Constitutional Union, and was not concerned with details of

its infrastructure. This matter was left entirely to those who

founded it. The King’s interest in this regard was confined to

blessing this campaign to realise the aspiration of restoring

constitutional life to Libya.

o It

was the founder of the

Libyan Constitutional Union and architect of the idea of restoring

the abandoned constitutional Legitimacy to its proper context,

through rallying around its symbol and around the country’s

constitution, who persuaded the King to give his consent and

blessing to it.

o When

the King gave his approval to this campaign, his implicit

stipulation was that he would not be directly involved in the

political activities of this affair. He had several reasons for

that, among the most important of which are his wish not to be seen

as violating the hospitality of the Egyptian authorities, who had

stipulated that he would not engage in political activities against

the ruling regime in

Libya. A

further equally important reason was the King’s advanced age and

poor health, which could not withstand such

burdensome

duties.

o Taking

into account all the above considerations, the king’s involvement in

the LCU was symbolic and stemmed from the necessity that his

positive response to this mission was considered both a religious

and nationalistic duty, imposed by the hardship endured by the

Libyan people under the cruel and brutal military dictatorship. The

king, who had maintained an ascetic lifestyle and abstained from the

luxuries of life and the trappings which power brought with it would

have never consented or give his blessing to this endeavour

had he not been assured by the architect of the idea of the Libyan Constitutional Union that this

would provide another great service to his nation, to whom he gave

his entire life.

Therefore

there was absolutely no cause to embarrass the King by asking him to

appoint Mr. Abdulhameed El-Bakoosh head of the Libyan Constitutional Union.

In spite

of all my above explanation to my honourable guest, he was adamant

in his refusal of our invitation for him to assume the leadership of

the LCU and steer it towards the aspiration of the Libyan nation,

and held on firmly to his aforementioned condition. I still did not

give up on this distinguished Libyan personality. I informed him

that the offer still stood and asked him to reconsider his final

decision in his own time.

I later

learnt that Mr. Bakoosh had no interest in leading the

Libyan Constitutional Union towards its designed goals when he sent

me publications of the “Libyan people’s Liberation Organisation” in

an obvious hint that he was intent on being actively involved in the

organisation which he established sometime earlier. [1].

*

*

*

*

*

During my

first visit to Egypt after this episode, I was greeted at Cairo

airport by Mr. Bakoosh with his customary courtesy. He expected me

to open the subject of his declining of my offer, but when I showed

no interest in the subject, he instigated a conversation in this

regard. In the context of justifying his refusal, he said that, on

the one hand, he had founded the

Libyan people’s Liberation Organisation in compliance with the

aspiration of the general ideological trend that was prevailing

amongst most of the Libyan opposition at the time. And that he saw

it as the proper political platform to confront the ruling regime in

Libya.

On the

other hand, the idea of the LCU, which was based on rallying around

the person of the King, did not conform with the general mood

currently rife among opponents of the regime. For King Idris was

not at that time a figure of total acceptance among Libyan

nationals, as indeed he was never a universally accepted figure,

either before or during the time of independence!

In his

zeal to articulate those justifications, my host forgot that, by

doing so he had contradicted himself in his previous declaration to

me during our meeting in Manchester, when he expressed his

admiration and total appreciation of the LCU’s approach and

manifesto.

*

*

*

*

*

It is perhaps worth drawing the reader’s attention here to the fact,

that I was absolutely certain that in the merging of the LCU’s,

initiative with Mr. Bakoosh’s numerous abilities and skills lied a

great chance to accomplish the task of ridding our country of the

despotic military regime.

In other words, joining Mr. Bakoosh’s political astuteness,

experienced leadership and wide range of regional and international

connections, with the solid ground and popular appeal of the

principals of the LCU would have inevitably led to the realisation

of the aspirations of the Libyan people.

I firmly believe that squandering that rare opportunity was a

tremendous loss to our national case.

To be continued…

Mohamed Ben Ghalbon

chairman@libyanconstitutionalunion.net

4th

August 2006

ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

[1]

“The Libyan people’s Liberation Organisation”, was one of the Libyan

opposition groupings which emerged at that time. We sent Mr.

Bakoosh a note of congratulations when he announced its

establishment. The name of this organisation was changed shortly

after its establishment to “The Libyan Liberation Organisation”,

bearing the slogans “Liberty, Fraternity and Justice”. The

organisation published a magazine named “The Liberation”. The first

Issue was published in April/May 1983. Towards the end of 1984 wide

cracks started to appear in the structure of this organisation

following a severe and bitter public clash between its founders Mr.

Bakoosh and Mr. Basheer El-Rabti, which eventually led to the

splitting of the organisation into two different bodies. Mr.

Bakoosh remained the head of the “Libyan Liberation Organisation”

and continued the publishing of “The Liberation” for a short while

before both the organisation and the magazine disappeared

completely. While Mr Rabti founded a new body he named “The Libyan

National Organisation”. This organisation published a magazine

named “Al-Mirsaad Allibi”.

|

|

Top of

the Page

Original Arabic

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

This part was published on

8th August 2006 the

following Libyan sites |

|

"Libya

Our Home" ,

"Libya Al-Mostakbal" , "Al-Manara"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

بسم

الله الرحمن الرحيم

Part (5)

(First published in Arabic on 28th July2006)

[2] Announcing the Establishment of the

Libyan Constitutional Union

Before

going any further in narrating details of the meetings which took

place between the Libyan Constitutional Union and various Libyan

notables and heads of Libyan opposition groups, I wish to mention

that during our intense campaign of contacting those personalities

to announce the establishment of the LCU, we spared no effort to

convince them of its essential idea of restoring constitutional

legitimacy to Libya.

Furthermore, we had tried all the means at our disposal to urge

these people to adopt this idea and unite under its banner.

We

made conscious efforts in this regard, to afford each one of those

personalities all the due respect, courtesy and recognition of past

and potential prominent future status. On certain occasions we

offered some of these personalities leadership of the LCU. This was

prompted by our keenness to advance the national interest ahead of

our own personal or partisan gains.

However, what had been hoped for from these personalities was not

realised and the results from dealing with them, were not only

disappointing, but shocking for the LCU. Some declared their enmity

towards me, the LCU and its founders (this will be dealt with in

greater detail when the subject of these personalities is raised in

its proper place in this article). This feeling of hostility was

one-sided. We did not reciprocate nor did we respond in kind

On the other hand, some of these Libyan personalities chose to

ignore the LCU completely, not only in their discussions and press

interviews but also in the text of their leaflets and distributed

publications. Among this last group one may mention the following:

Mr Mansour Alkikhia (may Allah bestow His mercies on him dead or

alive), Dr Muhammad Almegrief[1],

Mr Abdulhamid El-bakoosh and Mr Mustafa Bin-Halim[2].

*

*

*

*

*

Muhammad El-Saifaat

As

mentioned in the first part of this series, I came across Haj El-Saifaat

when I had contacted him (in August 1981) to ask him if he would

inform the intermediary between King Idris and myself about my stay

at my father’s house in Alexandria and my telephone number there[3]

Mr. El-Saifaat

did not like, at all, the fact that I had bypassed him and contacted

the late King through a person other than himself without consulting

him or seeking his permission. El-Saifaat saw himself, as we said

earlier, as the warden of the King’s private and public affairs. He

thought that any contact with the King concerning any matter, big or

small, should only be through him, with his personal agreement and

consent.

And from

then on, this veteran Libyan personality, who enjoyed widespread

popularity among many Libyans, declared his enmity towards me

unnecessarily and without any justification. He was responsible for

an intense campaign of vilification and slander against me

personally and my political orientation as embodied in the

establishment of the

Libyan Constitutional Union,

and rarely missed a chance when he met a group of Libyans, on any

occasion, to attack me and the idea of the LCU.

He was

able to spread his campaign due to his numerous contacts with Libyan

personalities and families that immigrated to Egypt at that time. He

enjoyed these contacts due to the special status that he had during

the monarchist era, which endeared him to many Libyan opponents of

the military regime which had toppled it.

The

affection that many Libyans had for Haj Mohammad El-Saifaat not only

made them listen to him, but made him their centre of attention and

their main source of information. In connection with this matter, a

contemporary of that era once disclosed to me that he considered El-Saifaat

a mobile news agency, who could through his exceptional

conversational skills convince his audience of whatever he wanted to

spread among them.

With this

background which was characterised and dominated by his limiting

vision of the national interest, Haj Mohammad El-Saifaat took me for

an enemy. He thought that I had made an unforgivable mistake when I

did not consult with him concerning my contact with King Idris, and

that I had not followed the protocol, that he himself had set.

Moreover,

El-Saifaat, who was born, raised and later worked in an environment

dominated by a tribal mentality, which dictates that there should be

no political change outside its area of influence.

An

important factor which should not be overlooked, and which is at the

crux of the Libyan make-up is the tribalistic nature of the

country. During the monarchy era certain tribes earned privileged

positions through their distinguished role in the armed struggle

which - coupled with the political campaigning that followed at a

later stage - led to the independence of the country and its

liberation from the hated Italian colonialism.

El-Saifaat’s tribe enjoyed a

prominent role in assuming positions of power which influenced

events throughout the monarchy

Through

this mindset, El-Saifaat saw in the emergence and coming to

prominence, of the LCU a political movement seeking to unite the

popular base around the Constitution and under the constitutionally

legitimate leader. Under these circumstances he saw the

establishment of the LCU as a violation of the rule upon which the

power structure of the monarchy regime was based.

This

particular concept of haj Mohammad El-Saifaat was shared by many

monarchy era personalities of tribal ancestry, whose tribes

participated in the struggle for independence. Furthermore, this

concept was the reason behind the dislike, which some Libyan

personalities had for the establishment in spite of their love,

affection and strong loyalty they felt for the King.

In other

words, the imposition of certain personalities to assume positions

of responsibility in the new born state, as recognition of the role

their tribes had played in the struggle during the Italian

occupation, gave rise to the feeling of antipathy among some

segments of the Libyan people including the

intelligentsia and those who belonged to the urban areas.

This happened after some of the tribal personalities emphasised

their tribal loyalty at the expense of their loyalty to the state

through advancing their tribes’ interests in preference to the

general interest of the country in certain affairs.

The

dissatisfaction of these groups arose because of the favouritism,

which the tribal elements were trying to impose within the Monarchy

regime. This dissatisfaction developed into a political hatred

between the two groups. This hatred was intensified by the

unconstitutional actions of certain tribal elements which led, with

the passing of time, to distort and undermine this refined political

system which unified the nation under a civilized and honourable

banner, immediately after its independence.

On the

other hand, this impassioned hatred ignited the flames of discord

inside the governing authority as embodied in some actions which

exceeded the proper bounds. These actions resulted from the tribal

intolerance and

zealotry

which found its clearest expression in the uncompromising tribal

stance leading to unacceptable political positions. The most

prominent of these positions took shape in the 1964 events which

expressed very clearly the intensity of

difference

in thinking between the city dwellers and some of the rural populace

who played an active role in the exercise of power in that era.

With this

in mind I will now return to the main subject of Haj Mohammad El-Saifaat’s

hostile stance towards me following his discovery of my direct

contact with the King without involving him in the matter. And more

importantly, his stand towards the

proposition that I outlined to the King in relation to the

establishment of the Libyan Constitutional Union whose core idea is

concerned with the return of the constitutional legitimacy to the

country.

Haj El-Saifaat

was dominated in this matter by his tribal bigotry. He perceived

this as an attempt to engulf the King in a national struggle aimed

at changing the government through an idea carrying within it the

seeds of success if the various currents of the Libyan opposition

would rally around it.

Therefore,

according to his line of reasoning, the success of the LCU through

elements belonging to the urban dwellers would lead to the exclusion

of the tribalistic elements, and so according to his assumption,

power would pass on to those who would be responsible for change, as

had been the case with some of the personalities of the tribal

entity following the country’s independence.

In this

way, Haj Mohammad El-Saifaat continued waging his attacks on my

person and The Libyan Constitutional Union in all the Libyan milieus

that he used to frequent at that time. His popularity among the

Libyan residents in Egypt helped him in his campaign, for almost

never a day passed without him being invited as a guest of honour by

one of the Libyan families in Egypt, and he took the opportunity to

slander me and the Libyan Constitutional Union to his hosts and

audience. To the extent that whenever he met my late father in a

social gathering of Libyans, resident in Egypt, he would start

venting his vehement criticism of my political orientations to him,

and condemn my efforts to achieve the desired general consensus on

the goals of the Libyan Constitutional Union. He actually went as

far as blaming my father for not forcing me to desist this

“incitement”.

In one

such occasion, my father had enough of hearing Haj El-Saifaat’s

repeated and exaggerated criticism, which were untruthful

and distorted. He said to him, “Please, Haj Muhammad, don’t talk to

me about this matter again. If you have any reservations or

criticism against my son’s political views go and speak to him by

yourself! My son is responsible for his actions. This is a matter of

his personal freedom and he is responsible for the political views

that he thinks suitable for the realisation of the national

interest.”

El-Saifaat

said to my father “but what your son is doing is in vain and will

not achieve anything for him. The Americans[4]

are on our side. Who is supporting your son?”

My father

replied “Allah and King Idris El-Senusi, are on the side of my son.

And if you think that he will not achieve anything and that his

efforts are in vain then let him alone and no harm or wrong will

befall anybody. Further, he will not harm you, especially, when you

are sure that you will achieve your desired aim by

being allied

with the

Americans.”

El-Saifaat

responded with indignation, “He is dispersing the efforts and

hindering our work”

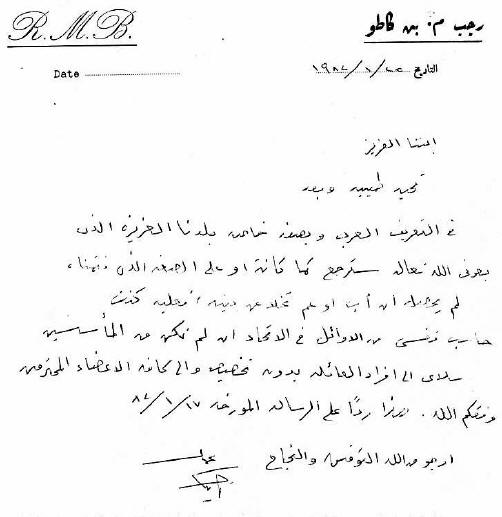

My letter

to Haj Mohamad El-Saifaat, which was dated 17th January

1982 and contained an insistent call for his cooperation and support

for the declared aims of the LCU[5] did not change his stance toward me and the LCU

To be continued…

Muhammad Ben Ghalbon

chairman@libyanconstitutionalunion.net

30 September 2006

ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

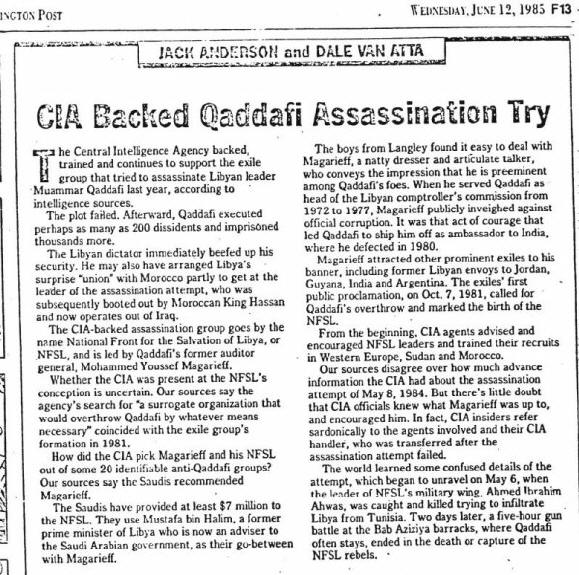

[1]

Many years after leaving the "National

Front for the Salvation of Libya”, Dr Mohammad Almegrief referred to

The LCU in his Book, “Libya Between The Past And The Present….Pages

From The Political History”. This mention of the Libyan

Constitutional Union is necessary in the context of the nature of

his subject, which in part deals with documenting the history of the

struggle of organisations and groups of the opposition against the

regime in Libya.

[2]

In a press interview conducted by Mohammad

Makhlouf with Mustafa Bin Halim, which was published in Al-Sharq Al-Awsat

newspaper (issue number 5239, 2 April 1993) Mr. Bin Halim was asked

about his opinion concerning the Libyan Opposition abroad at that

time. In his answer Mr. Bin Halim mentioned the known opposition

groups and deliberately ignored the Libyan Constitutional Union.

Makhlouf followed that answer with the Question, “And what about the

LCU?” Bin Halim answered, pretending his total ignorance of the LCU

and lack of his personal knowledge of me, by saying, “Who are they?

I do not know them, therefore I do not comment on them.”

What is

so extraordinary and confounding in this matter is that Bin Halim,

as we shall see later when we discuss his stance, was among the

first personalities that had been contacted to be informed about the

establishment of the LCU and was urged to support its idea.

Furthermore, what makes Bin Halim’s stance confounding and

eccentric, as is expressed in his misleading answer, is the fact

that he is a relation of mine. He is in fact my cousin (my father’s

sister’s son). This is really extraordinary and unusual and one can

find for it neither an answer nor an explanation.

[3]

Part 2 of this series:

http://www.libya-almostakbal.com/MinbarAlkottab/July2006/mohamed_ben_ghalboon_lcu210706p2en.htm

[4]

What is meant here is the American support for the “National Front

for the Salvation of Libya” which Haj Mohammad El-Saifaat was one of

its prominent founders.

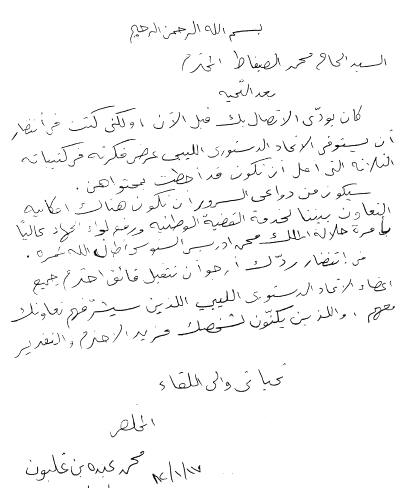

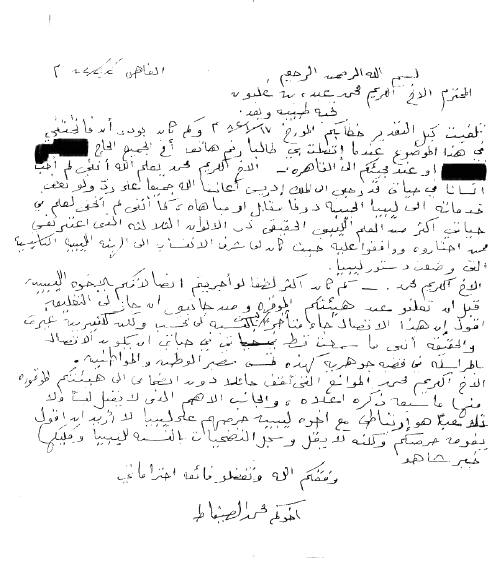

[5]

A letter had been sent to Haj Mohammad El-Saifaat, as a part of the

above mentioned campaign to contact prominent national figures. His

reply was negative. (Below are copies of all the correspondence we

exchanged with him)

-----------------------------

Many thanks to Mustafa for undertaking the arduous task of

translating this document from Arabic

Also, a big thank you to Obaid for editing it

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Appendices

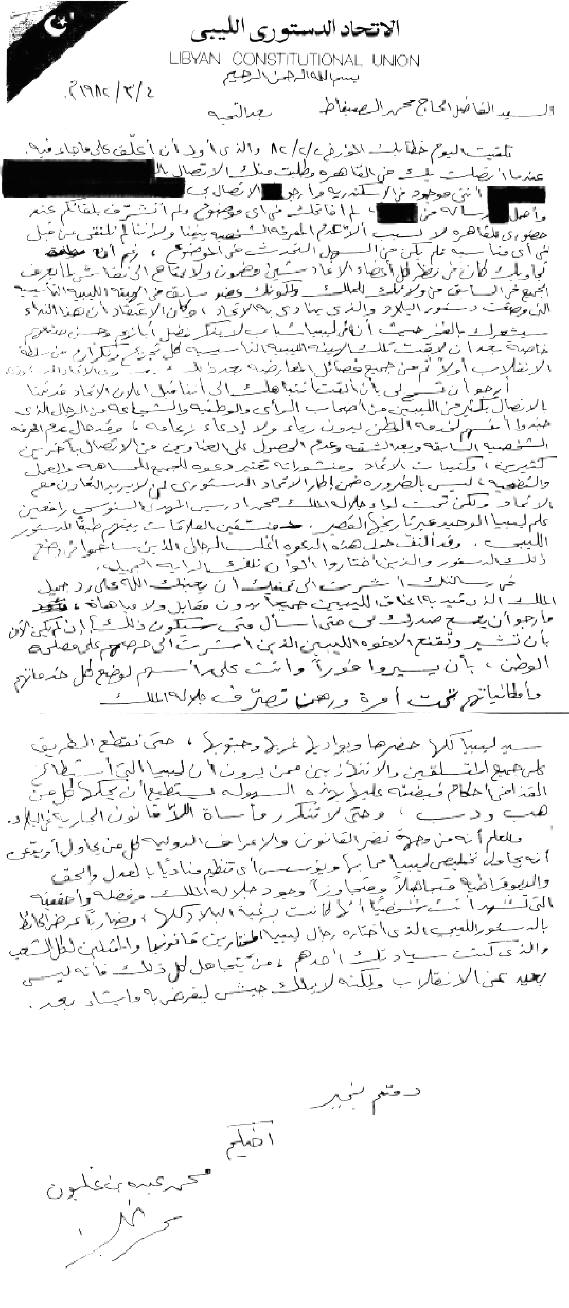

Appendix 1:

A translation of the LCU’s letter to

Haj Muhammad El-Saifaat dated 17th

January 1982

In the Name of Allah,

the Beneficent, the Merciful

The honourable

Haj Mohammad El-Saifaat,

17/01/82

Greetings

I wanted to contact you earlier, but was waiting

for the Libyan Constitutional Union to complete introducing its idea

through its three booklets, which I hope you are now familiar with.

We would be happy if there is a possibility of

working together to serve the Libyan cause, and raise the banner of

resistance aloft under the command of His Majesty King Muhammad

Idris El-Senussi (May Allah give him a long life).

While waiting for your reply, please accept the

respects of all members of the Libyan Constitutional Union, who

would be honoured to work with you, and who all hold your person in

high esteem.

Compliments, until we meet

Yours sincerely

Muhammad Abdu Ben Ghalbon

** * **

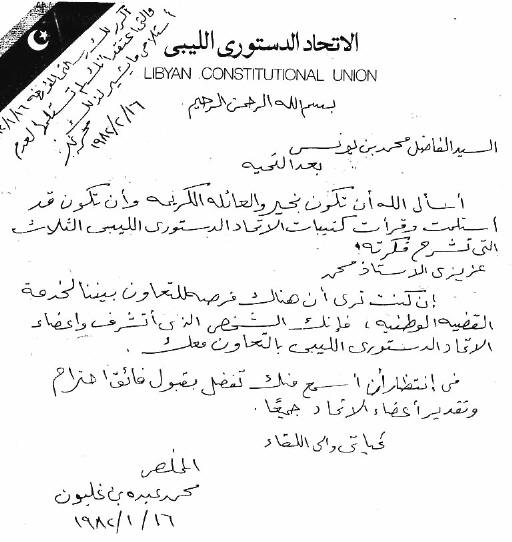

Appendix 2:

A translation of Haj Muhammad El-Saifaat’s

reply dated 2nd February 1982

In the Name of Allah,

the Beneficent, the Merciful

The honourable brother Muhammad Abdu Ben Ghalbon,

Greetings

Cairo : 02/02/82

I gratefully received your letter dated 17th

January 1982. I dearly wished that you opened this subject with me

when you contacted me to request the phone number of our brother Haj

(.....)[1], or when you came to

Cairo.

Honourable brother, God knows that I never loved

anybody in my entire life as much as I loved King Idris, may Allah

help us all to repay him for at least some of his services to our

beloved Libya, which he offered the country without asking anything

in return. Also, I never bowed to any flag more than the real

Libyan flag with its three colours, which I consider myself among

those who selected and approved it, as I was honoured to be a member

of the original Libyan body which formed Libya’s Constitution.

Honourable brother Muhammad; it would have been

more courteous had you contacted the Libyan brothers prior to

announcing your esteemed establishment. On my part, if I may

comment, I would say that your contact came too late, not just for

me, but for many others. The truth is, I have never in my whole

life heard of contacts regarding such a vital issue, that concerns

the future of the homeland and the nation, being made by

correspondence.

Honourable brother Muhammad; some of the

obstacles that prevent me from joining your esteemed establishment

are those I mentioned above. More importantly, however, the part

that is beyond doubt or trickery is that I am committed to some

Libyan brothers whose concern for Libya, I would not say is superior

to yours, but I would say is not inferior. The record of sacrifice

for Libya and its monarch is the best witness.

May

god help you

Respectfully; Your brother

Mohammad El-Saifaat

[1]

Omitted from document to protect identity of the person

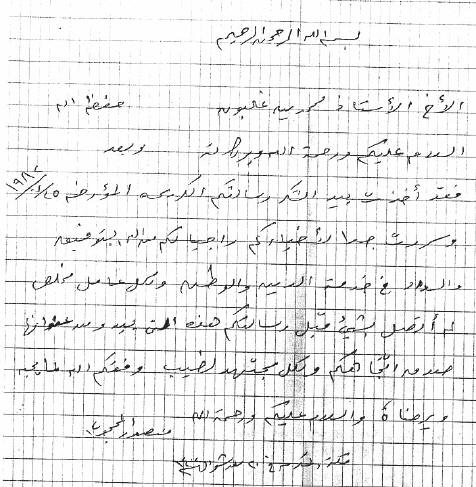

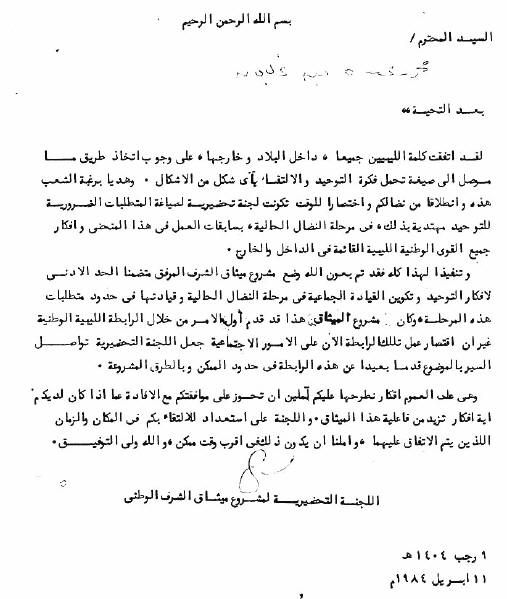

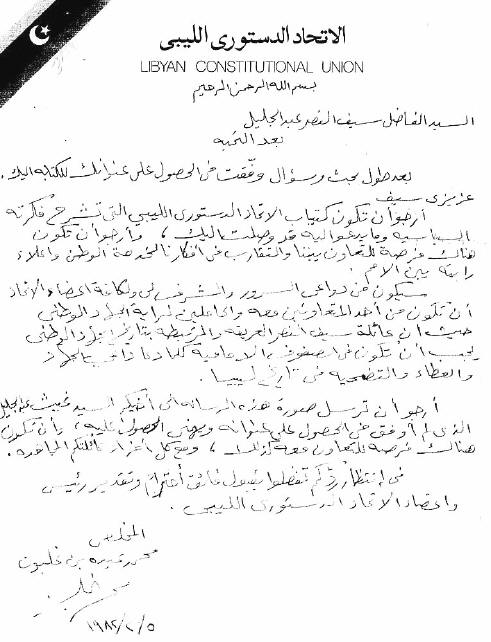

Appendix 3:

A translation of LCU Letter to Haj

Muhammad El-Saifaat dated 4th March 1982

In the

Name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful

The honourable Haj Mohammad El-saifaat

4/3/1982

Greetings

I have today received your letter (dated 2/2/82)

and I would like to comment on its content.

When I contacted you in Cairo and asked you to

get in touch with (.....) to tell them that I was in Alexandria and

I would like them to get in touch with me as I had a message from

(…), I did not discuss any subject with you. Furthermore, I did not

have the honour of meeting you when I was in Cairo, simply because

we did not know each other, nor had we met at any occasion

beforehand. Therefore it was not easy to talk about the subject.

However, all of the LCU members thought that your response was

unquestionably guaranteed to be positive, as a result of what

everybody knows about your past loyalty to the King and your being a

former member of the National Constituent Assembly which wrote the

country’s constitution. This Constitution is what The Libyan

Constitutional Union is calling for.

The belief was that this call would make you

particularly proud of the fact that some young people from Libya are

grateful to their forefathers and are not denying their glorious

deeds. This was especially so as the National Constituent Assembly

was the target of ingratitude and slander, firstly from the coup

d’etat government, and then from all the opposition groups with the

exception of the LCU.

Please permit me to direct your attention to the

fact that before announcing the establishment of the LCU we had

contacted many Libyans known for their vocal opinion, patriotism and

courage and who dedicated themselves to the service of the homeland

without adulation or claims of leadership. Lack of personal

knowledge of many others and the inability to obtain their addresses

prevented us from contacting them.

Furthermore, the LCU booklets and publications

are considered an invitation for all to participate, work and

sacrifice - not necessarily within the framework of the LCU, for

those who do not want to co-operate with it - but under the banner

of His Majesty King Mohammad Idris El-Mahdy El-Sennusi, raising the

only flag that Libya ever had during its short history and

coordinating the relations among themselves according to the Libyan

Constitution. Most of the people, who participated in the writing

of the Constitution, were united in following these ideals. These

are the same men who chose the colours of that beautiful flag.

You referred in your letter to your wish for the

help of Allah (SWT) to enable you to repay the debt to the King and

return his favour, which he bestowed on all the Libyan people with

neither boasting nor asking them for anything in return, and which

made all the Libyans indebted to him.

I am relying on your magnanimity to allow me to

ask you when this debt will be repaid if not now by advising and

convincing the Libyan brothers, who you stated in your letter are

conscientious about the interests of the

homeland, to make themselves and services – with yourself at the

forefront - at the immediate disposal of his majesty the King.

For the King, is the master of all Libya, Urban, Bedouin,

West and South. In this way we combat the opportunists who saw in

the ease with which Gaddafi tightened his grip on Libya an

invitation for them to be its next rulers.

Furthermore, this is also the way to prevent the

sad state of lawlessness prevailing in Libya from ever happening

again.

It is also to be noted that according to

International Law and legal customs, anybody who attempts, or claims

to be attempting, to rescue Libya from its current woes by

establishing an organisation that calls for justice, right and

democracy while ignoring and bypassing the King, whose rights and

entitlement were granted by the whole country, as you can personally

attest to - or one who dispenses with the Constitution which was

written by men, including you yourself, who were legally chosen by

the Libyan people as their representatives - is not that much

different to the one who staged the coup d’etat. The only

difference is they lack the army, as of yet, to impose their will.

May you always be well,

Your brother

Muhammad Abdu Ben Ghalbon

(......) Omitted from document to protect

identity of the person.

|

|

This part was published on

30th September 2006 the

following Libyan sites |

|

"Libya

Our Home" ,

"Libya Al-Mostakbal"

|

|

|

|

|

|

Top of

the Page Original Arabic

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|